Fermi Improves Its Vision For Thunderstorm Gamma-ray Flashes

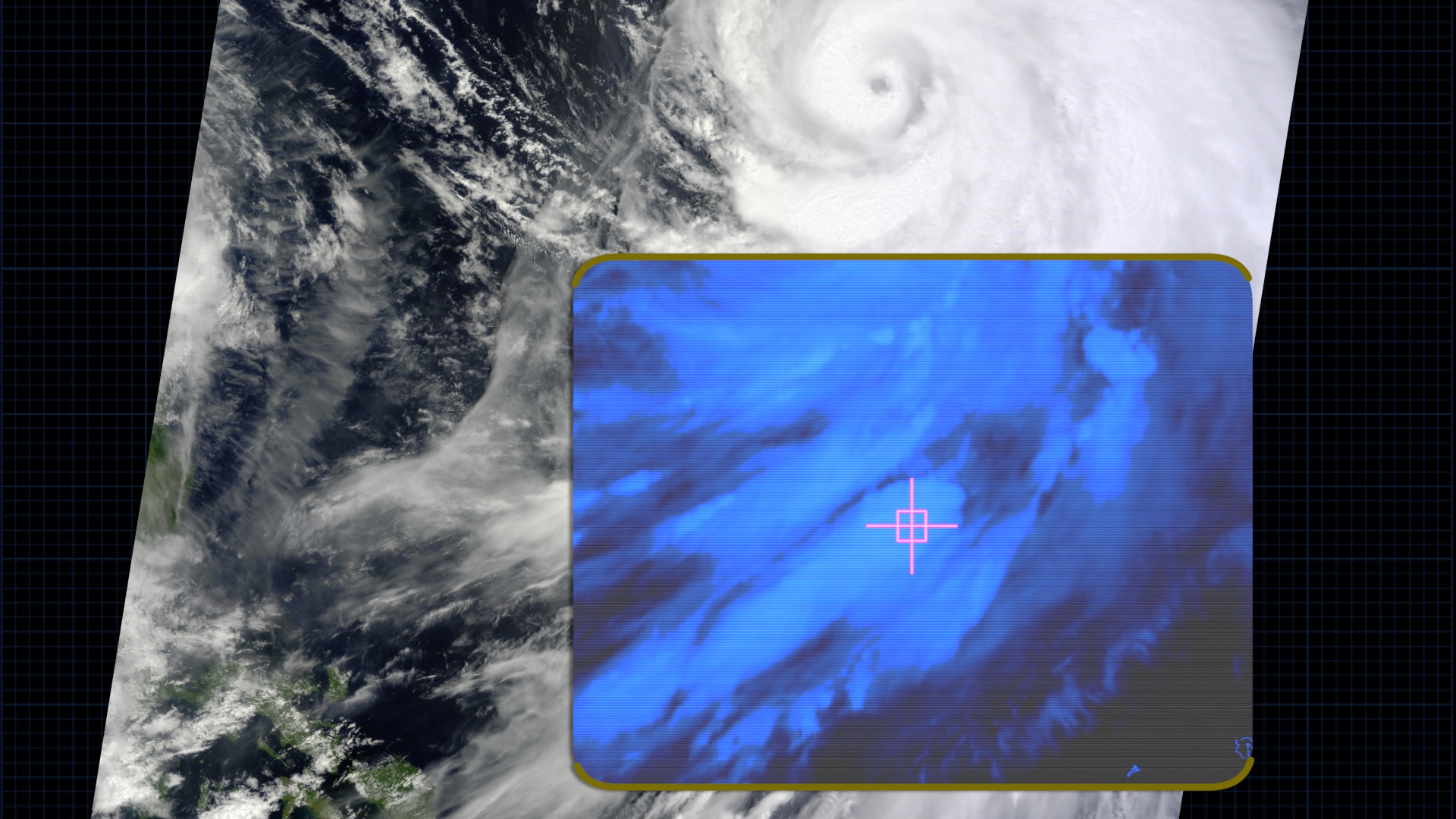

Thanks to improved data analysis techniques and a new operating mode, the Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM) aboard NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope is now 10 times better at catching the brief outbursts of high-energy light mysteriously produced above thunderstorms.

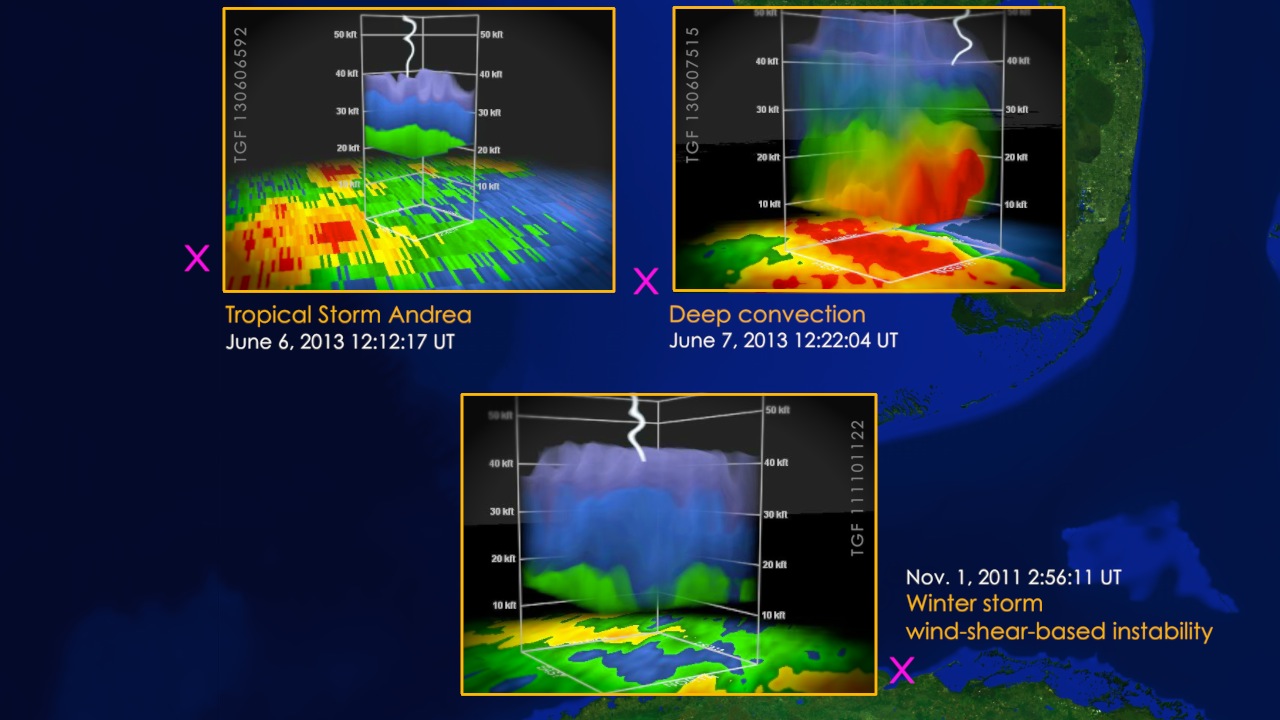

The outbursts, known as terrestrial gamma-ray flashes (TGFs), last only a few thousandths of a second, but their gamma rays rank among the highest-energy light that naturally occurs on Earth. The enhanced GBM discovery rate helped scientists show most TGFs also generate a strong burst of radio waves, a finding that will change how scientists study this poorly understood phenomenon.

Lightning emits a broad range of very low frequency (VLF) radio waves, often heard as pop-and-crackle static when listening to AM radio. The World Wide Lightning Location Network (WWLLN), a research collaboration operated by the University of Washington in Seattle, routinely detects these radio signals and uses them to pinpoint the location of lightning discharges anywhere on the globe to within about 12 miles (20 km).

Scientists have known for a long time TGFs were linked to strong VLF bursts, but they interpreted these signals as originating from lightning strokes somehow associated with the gamma-ray emission.

"Instead, we've found when a strong radio burst occurs almost simultaneously with a TGF, the radio emission is coming from the TGF itself," said co-author Michael Briggs, a member of the GBM team.

The researchers identified much weaker radio bursts that occur up to several thousandths of a second before or after a TGF. They interpret these signals as intracloud lightning strokes related to, but not created by, the gamma-ray flash.

Scientists suspect TGFs arise from the strong electric fields near the tops of thunderstorms. Under certain conditions, the field becomes strong enough that it drives a high-speed upward avalanche of electrons, which give off gamma rays when they are deflected by air molecules.

"What's new here is that the same electron avalanche likely responsible for the gamma-ray emission also produces the VLF radio bursts, and this gives us a new window into understanding this phenomenon," said Joseph Dwyer, a physics professor at the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne, Fla., and a member of the study team.

Because the WWLLN radio positions are far more precise than those based on Fermi's orbit, scientists will develop a much clearer picture of where TGFs occur and perhaps which types of thunderstorms tend to produce them.

Watch this video on YouTube.

Lightning in the clouds is directly linked to events that produce some of the highest-energy light naturally made on Earth: terrestrial gamma-ray flashes (TGFs). An instrument aboard NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was recently fine-tuned to better catch TGFs, and this allowed scientists to discover that TGFs emit radio waves, too.

For complete transcript, click here.

This image, taken in May 2008 as the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was being readied for launch, highlights the detectors of the spacecraft's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM). The GBM is an array of 14 crystal detectors designed for transient lower-energy gamma-ray outbursts, such as TGFs. Labeled.

Credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

This image, taken in May 2008 as the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was being readied for launch, highlights the detectors of the spacecraft's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM). The GBM is an array of 14 crystal detectors designed for transient lower-energy gamma-ray outbursts, such as TGFs. Unlabeled.

Credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

This image, taken in May 2008 as the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope was being readied for launch, highlights the detectors of the spacecraft's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM). The GBM is an array of 14 crystal detectors designed for transient lower-energy gamma-ray outbursts, such as TGFs. Uncropped.

Credit: NASA/Jim Grossmann

For More Information

Credits

Please give credit for this item to:

NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center. However, individual images should be credited as indicated above.

-

Animators

- Walt Feimer (HTSI)

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

- Hal Pierce (SSAI)

- Joseph Dwyer (FIT)

-

Video editor

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Narrator

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Producer

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

-

Scientists

- Valerie Connaughton (NASA MSFC/University of Alabama)

- Michael Briggs (NASA/MSFC)

-

Writers

- Francis Reddy (Syneren Technologies)

- Scott Wiessinger (USRA)

Release date

This page was originally published on Thursday, December 6, 2012.

This page was last updated on Wednesday, May 3, 2023 at 1:52 PM EDT.

Missions

This visualization is related to the following missions:Series

This visualization can be found in the following series:Tapes

This visualization originally appeared on the following tapes:-

Fermi TGF Radio

(ID: 2012115)

Friday, November 16, 2012 at 5:00AM

Produced by - Robert Crippen (NASA)

Datasets used in this visualization

-

[Fermi]

ID: 687 -

Fermi GBM TGF (Terrestrial Gamma Flashes) [Fermi: Gamma Ray Burst Monitor]

ID: 706

Note: While we identify the data sets used in these visualizations, we do not store any further details, nor the data sets themselves on our site.